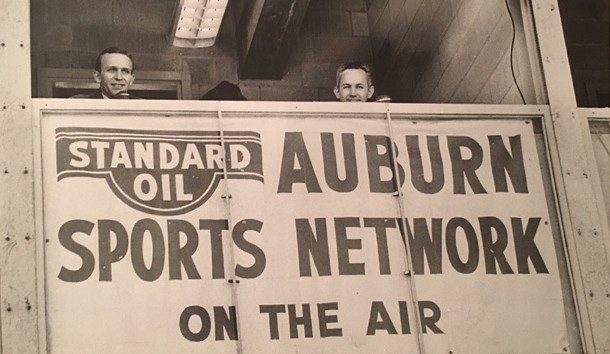

Charlie Davis in the Auburn Network broadcast booth in Cliff Hare Stadium in the 1950s

There was a wooden cabinet in the corner of my mother’s kitchen in Rock Creek. It was about six-feet high and my dad had painted it with some kind of shiny lacquer. It had doors on the bottom that opened to the space where mother kept some antique dishes that had belonged to her grandmother. Above those doors were three shelves that held assorted things – a napkin holder, salt and pepper shakers, an electric clock … and a portable radio.

I only remember things about the radio. It was hard plastic, bright red with a black antenna on top, the kind that would swivel in any direction to hunt a better signal. It was a Motorola, significant because my wife later worked for that communications giant for about 20 years.

My mother was the registrar/secretary at the local grammar school in the late 1950s, so she got up early to leave in time to open the school every day. Since she had to get up early, I did, too.

Every weekday morning, I sat at the kitchen table, back to the corner cabinet, eating a bowl of oatmeal. Behind me that red plastic radio would be playing big band music and blaring out the most irritating greeting, something like this … “Rise and shine. It’s the Early Risers Club and it’s a great day in Birmingham!”

It was still dark; my eyes were half open; I was listening to Tommy Dorsey and eating oatmeal.

What was so great about that, you may ask?

Well, that voice was the show’s host Charlie Davis, a World War II veteran who served with honor in the South Pacific, a young man who contracted polio after the war, and the color analyst and network coordinator for Auburn football. Of course, I didn’t know all that back then. He was just the guy who ruined my mornings while mother gave me oatmeal.

Charlie Davis died a few days ago, and when he did, we lost a radio and television icon, a dedicated civic leader, and one of the most loyal and longtime members of the Auburn family.

Charlie was born in Birmingham and raised in Alexander City, a small town down Highway 280 between Sylacauga and Opelika. He was a student at Benjamin Russell High School when Japanese warplanes attacked the American fleet in Pearl Harbor plunging the United States into World War II. After high school graduation, he became a member of the U.S. Army.

That started Charlie on a life that was … by any measure … diverse, interesting, meaningful, rewarding, successful.

During the war, he served in New Caledonia in the South Pacific, stormed the beaches at Bougainville, and was among American soldiers training for a possible invasion of Japan. He earned the Bronze Star.

He enrolled at the University of Alabama after the war, majored in Radio, joined a fraternity and was a drummer in the Cavaliers big band orchestra. After college days, he started a radio station in Greenville, Ala., and worked in the industry around the Southeast. In 1954, he was hired by WAPI radio and television in Birmingham as their mid-day disc jockey. Before he left the station in 1970, he had served as program director, news director and news anchor, as well as host of that morning radio show.

After a brief stint in Dothan as a television station general manager, he moved back to the Birmingham area permanently, where he owned an advertising agency and a restaurant and served for a decade as public relations director for Carraway Hospitals. He served on the Vestavia Hills City Council, elected six times, serving 24 years, the longest tenure in city history.

He was an objective journalist who reported on some of the most tumultuous events in Birmingham history in the 1950s and 1960s, interviewing civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. and Birmingham public safety commissioner Bull Connor, covering the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and the political campaigns of George Wallace.

He was a dedicated, conservative civic leader, willing to sacrifice his talents, time and connections to help the city of Vestavia, the Birmingham community and his beloved home state.

He was a husband, a father, a grandfather, a friend.

But, more than anything else, Charlie Davis was known for being Auburn.

That came naturally for Charlie having grown up in Alexander City, not far from Auburn, the team that he pulled for as a young man. But, some people couldn’t understand it. How could an Alabama graduate become the Auburn football broadcaster?

“Right after I was hired, a lot of Auburn people would challenge me,” he recalled not long ago. “They would ask ‘How did you get this job? You went to Alabama.’ One day in the Field House, I ran into Coach Jordan and told him what had happened. He said, ‘Charlie, you just tell them that I chose you for this job, then see what they say.’ That’s what I did and that’s when all that stopped.”

Over the years, Charlie more than proved his devotion to Auburn. He had a close personal and working relationship with legendary head coach Ralph “Shug” Jordan and iconic athletic director Jeff Beard. Auburn football was escaping from post-war mediocrity, quickly becoming a national power, heading toward the program’s first national championship since 1913 and as a young journalist, a graduate from “that other school,” he had been invited to be part of the experience. He never lost appreciation for the opportunity he was given.

His on-air career was with four Auburn play-by-play announcers … Dan Daniels, Tom Hamlin, Buddy Rutledge and Gary Sanders. They told Auburn listeners about Heisman and Outland Award winners, classic games, heartbreaking losses and historic wins. Fob James, Lloyd Nix, Zeke Smith, Tucker Frederickson, Pat Sullivan, Terry Beasley and so many others all played games called by Charlie Davis.

His years with Buddy Rutledge were especially unique. Charlie was stricken with polio in the early 1950s, damaging his right leg, impacting his mobility the rest of his life. Rutledge, a former Georgia football player, was paralyzed with polio, confined to a wheelchair. In those days, stadiums didn’t have press box elevators, so Charlie had to help with moving Buddy and freshman players would carry Rutledge up to the press box.

“We had to be the only broadcast team ever where both guys were polio victims,” he said. “What were the chances of that?”

Slim chances, for sure. But neither of them ever allowed the handicap to affect their job. Most Auburn fans never even knew it. That’s how Charlie was. His foremost obligation was to professionalism and accuracy, making sure that his audience was informed and entertained. He appreciated loyalty to other teams, but he was an Auburn man, proud to be an Auburn man, and you weren’t around him long before you knew it.

Charlie became my father-in-law … actually my stepfather-in-law … 23 years ago when he married my wife’s mother, Dodie Phillips. Her first husband had died in 1989 and Charlie’s first wife passed away two years later.

Over the years, we talked many times about games that we both had attended and covered, athletes that we had interviewed, people in sports media that were mutual friends. He talked about his steadfast faith in God, belief in country, love for family, and passion for Auburn.

And, I never let Charlie forget about how I was first introduced to him, back in my mother’s kitchen, eating oatmeal. I let him know that I never developed an appreciation for oatmeal. But, that I did develop the greatest appreciation for Charlie’s life and for the privilege to know him.

Countless people who never actually got to know Charlie Davis felt like they did. He made a difference in lives, informed and entertained them, and made it a “great day” for so many.

They’ll all remember him and miss him. We all will.

Thank you for everything, Charlie.

Rest in peace … and War Eagle!